Chapter 10 – Transphysical Humans

Up to this point, we have approached the topic of a new metaphysics from the bottom up—beginning with a definition of actual occasions, and then seeing how to build an understanding of reality that not only includes the physical world familiar to science but also explains the existence of transphysical worlds. In this chapter, I will now approach the subject from a different perspective—starting from our everyday waking experience and what we call “common sense.”

In the modern era, conditioned by the ideas of the European Enlightenment, the standard view of reality is based on two basic—and for the most part unquestioned—assumptions. First, that the physical world is the whole of the actual world; and second, that the physical world is vacuous—that it is not conscious, has no aim, and has no value for itself.

Following Whitehead, I reject both of these assumptions as fundamentally incoherent—mainly because they impel modern philosophy and science into the impasse of the mind-body problem and the quicksand of modern epistemology. If we view the world through the lens of those two metaphysical assumptions, we are effectively forced to conclude that we can never truly know anything about reality. Consciousness, and with it knowledge, becomes incomprehensible at best and impossible at worst.

Clearly, then, we need a new set of basic metaphysical assumptions. And that is what we are exploring in this book.

These new metaphysical ideas are, admittedly, radical—necessarily so, if we are to come to terms with the phenomena of consciousness, survival of personality after death, and reincarnation. However, just as relativity theory embraced and expanded on Newtonian physics, the model of a transphysical world that I am proposing includes, while transcending, the ideas of scientific materialism. On the one hand, Newton’s mechanics can be abstracted from relativity theory by ignoring velocities that are “too high.” In the same way, materialism can be abstracted from this new metaphysics by ignoring actual occasions whose grades are “too high.” The point I want to emphasize from the start is that materialism does express important truths, but that these are a subset of a larger body of truths illuminated by this new metaphysical system that embraces both the physical and transphysical worlds. There is no fundamental contradiction or incompatibility between these two systems.

My starting point, therefore—and, I believe, this must be the starting point of any successful and comprehensive cosmology—is to reject the notion of vacuous actuality. Reality, all that exists, consists of actual occasions, and each actual occasion is necessarily and intrinsically sentient.

Each of us, in each moment of our existence, is an actual occasion. We actually exist at this moment in time. There is nothing mysterious or obscure about an actual occasion—it is precisely the type of thing that you are in each moment of your stream of being. Each of us is purposeful, thoughtful, imaginative, volitional, and decisive. We know for certain that we are actual (because, as Descartes so dramatically demonstrated, to doubt or deny our own actuality, is to affirm it). Given this, we can—and do—posit ourselves as paradigm examples of actual entities.

Taking this process view as our starting point, we open the way for a profound rethinking of the subject-object relationship. We no longer think of subjects and objects as two distinct kinds of things. Everything that actually exists is both subject and object—a subject for itself, and an object for others. From the perspective of process metaphysics, we can now see the distinction between subject and object as a temporal difference. Actual occasions are subjective during the process of actualization, and, having actualized, they become objects for future subjects. Philosopher Christian de Quincey referred to this new process view of the mind-body relationship as “past matter, present mind.”[1] Subjects exist now, in the present moment. However, as soon as the present moment is complete, it expires and becomes an object in the past, which can then be apprehended by subjects that exist in the new present moment. Each moment of our existence is the formation of a new event, and that event is an object for future subjects.

Once we base our metaphysics on the assumption of intrinsically sentient actual entities, the hoary mind-body problem is resolved. We see that mind (subject) and matter (substance) are related as phases in process, not as radically different things interacting in space. Contrast this new, commonsense view of reality—based on our own intimate experience—with the standard materialist alternative. If we begin with the assumption that actual entities (e.g., atoms) are vacuous and insentient then it becomes impossible to coherently account for the existence of conscious beings like us. Yes, to a great extent, materialist metaphysics can account for the behavior of inorganic entities, such as atoms and molecules. But it fails, utterly, to account for the nature and behavior of entities like us who can appreciate value, make choices, and decide on actual outcomes. If the materialists were right, and if we were nothing but automatic interactions of dead atoms, how could it be that we are sentient?

To avoid this impasse, I follow Whitehead, and propose that atoms and molecules—indeed, all actual entities—are just like us, though with varying degrees of sentience, purpose, intentionality, volition, and choice. Once we make this move, we have entered a very different cosmology, a very different world. This new ontological perspective opens the way, as we have seen, for an entirely different understanding of matter.

Both process metaphysics and quantum mechanics tell us that matter is a dynamic texture of events. But do they both reveal the same kind of events? On the face of it, the answer would appear to be “no.” The events studied by quantum physics reveal nothing but inorganic, low-grade matter—so low grade, in fact, most practicing scientists assume that such matter is thoroughly insentient. However, a very different species of events is revealed in our own experience: the events that constitute our ongoing stream of embodied consciousness. Clearly, these high-grade events are altogether different. Human beings are not at all like electrons or protons—even though we are made up of those subatomic events. In short, living matter is radically different from inorganic matter.

Given this obvious distinction, we may ask: “How are these two kinds of matter, these different species of events, related?” In the context of materialism, we can give no adequate answer to this question. In this book, I have been proposing that reality consists of a hierarchy of events—from those with minimal awareness (in the sub-atomic realm), to events with varying degrees of awareness throughout the living world, all the way up to the self-reflective awareness of humans and other higher animals; and, quite possibly, beyond the human and animal realm into domains explored by the great yogis and mystics.[2]

It follows, therefore, that we can interpret the world in terms of different grades of matter that vary in the degree of their conscious, purposeful participation in the creative advance. I first came across this general cosmological vision in the work of the Theosophical movement. Whatever their failings might have been, they succeeded in developing and delivering a compelling cosmology that surpassed in its comprehensiveness and inclusiveness the then prevailing cosmology inspired by scientific materialism.

Theosophical Cosmology

The Theosophists tried to express the notion of grades of matter, where each grade constituted its own world or “plane.” However, they attempted to distinguish between different levels of grade by relying on the physical notion of “density.” They spoke about a hierarchy in which solid matter was at the base level, with six higher levels, each with progressively less density. They even tried to locate the transphysical worlds in a “fourth dimension.” Since then, the notion of density has been replaced by “frequency,” where the “higher realms” are imagined as operating at higher “frequencies” and higher “energies.”[3] In contemporary New Age circles, metaphors of frequency and dimension tend to dominate discussions of transphysical worlds.

Attempts to define or describe transphysical worlds in the language of physics are philosophically naïve. In this work, I am offering a new, and more robust, metaphysical treatment of the transphysical worlds. For example, rather than defining “higher” matter in terms of “frequency” or “density,”I am proposing that “higher” matter is more profoundly animated by imagination and thought than lower grade matter. This formulation, I believe, accounts far more adequately for the experiences on which our knowledge of the transphysical world is based.

Rather than referring to “higher dimensions” to account for the “where” of the transphysical worlds, I am proposing that we account for the transphysical worlds in terms of meta-geometries that are less restrictive than the metrical geometry of physical space, irrespective of how many dimensions it may have.

Talk of “meta-geometries” can sound abstract and remote from the concerns of daily life. I want to bring metaphysics down to Earth, therefore, by describing our familiar experience in terms of these ideas. Note, that in this discussion in particular—and in this book in general—I am parsing the hierarchy of material into three grades: physical, vital, and mental.

Different Kinds of Material

We can understand the material of our own bodies and the world around us in different ways. For example, following modern science, we tend to think of our bodies “out there” in the physical world; at the same time, we also experience our bodies from “in here.” But, given this scientific understanding, the exact nature of the relationship between our bodies and our experience is shrouded in deep confusion.

How, exactly, could we have a conscious inner experience of a body that is entirely devoid of, and outside, experience?

In the new way of understanding, outlined in this book, our bodies are composed of dual-aspect actual occasions that are causally effective on the outside and drops of experience on the inside. Furthermore, the transmission of energy among these actual occasions involves the partial reproduction of the experience of earlier occasions in the experience of later occasions. Our bodily experience is our partial reproduction of the experiences of the occasions that make up our bodies.

Try this exercise: Describe to yourself what it feels like to have a body. Note that even with eyes closed, you can still feel and roughly distinguish different locations in your body. We could say that the body is an inner time-space. Now describe to yourself the time-space inside your body and the difference between this and the time-space outside your body. Feel where in your body “you” are most centered. How does the time-space around you feel compared to the time-space at the periphery of your body? Now imagine every center of intensity in the time-space of your body as a living consciousness. Imagine the time-space of your body as a communion of conscious events.

Keeping this experience in mind, let’s now explore the various kinds of actual occasions that make up our bodies and the worlds in which they exist.

Inorganic Actual Occasions

We know very well how to identify and locate inorganic occasions. Our civilization has developed extraordinary mastery of physical occasions. But now let’s look more closely at physical occasions from our new point of view.

Some of our bodily organs are, or come very close to being, inorganic occasions—for example, the outer parts of our bones, our fingernails, tooth enamel, or strands of hair. Our relationship to these parts of our bodies is somewhat ambiguous. On the one hand, we identify them as parts of us, but, on the other, because we cannot really feel what happens to them, they also seem somewhat external to us. Hair is a good example because it is midway between being an actual body part and a piece of clothing. It is by virtue of these inorganic bodily component that we participate in the inorganic world around us. Not only our organs, but each individual cell in our bodies has its own inorganic parts—for example macromolecules such as proteins, DNA, and lipids. If I want to grasp a physical object, I move my hand in such a way that the molecules of my skin cells bump up against the molecules of that object.

Vital Matter

Suppose I were to say “imagine a mountain, and fill in as many details as you possibly can.” In carrying out this task, you would construct an image. You might start from a memory, or you might give yourself freedom to make up any part of the picture. In any case, there would be a kind of work going on as the image formed. In terms of our new ontology, this is an example of working with imaginal, or vital, occasions.

When we work with vital occasions (or “imaginal matter”), we don’t use our hands. Rather, we work with vital occasions by making decisions and applying our will. For this reason, our relationship to vital occasions is more intimate than to physical occasions. We think of vital occasions as somehow internal to ourselves, whereas we think of physical occasions as somehow external. And yet, our imaginal work is a crucial link between ourselves and the physical world.

When we use our hands to interact with physical occasions, particularly if we are being attentive and deliberate, we first imagine what we want our hands to do, and then our hands do it. Suppose, for example, I to ask you to raise your right arm so that it is parallel to the floor. You would hear theses words, and get a sense, in your imagination, of what I am asking. Then you would decide whether or not to cooperate with me and then, and only then, would your arm rise. Our manual habits are formed under the direction of active attention and imagination, and even our inherited habits reflect the creativity and careful attention of our evolutionary ancestors. The conclusion here is that before we can work with physical occasions, we must first work with imaginal occasions. In an important sense, vital occasions mediate between our minds and our physical bodies. In order to move our physical bodies, we must first move our vital bodies.

Vital occasions not only allows us to move our bodies in ways we find interesting and useful, they also enable us to perceive the world as we do. To get a sense of this, think about the physical world as the one explored by physics. It is just a collection of inorganic, low-grade events in systematic patterns of causal interaction. The physical world may take the form of suns, planets, rocks and so forth, but the low-grade events that embody these forms are not aware of those forms. For example, the atoms in a rock seem to be intent on maintaining their own stability by maintaining a steady relationship with their neighboring atoms, but do not seem to act as if they know about the role of the rock in the larger geological situation. We, on the other hand, do recognize the rock as a relatively enduring entity, and, further, we recognize the rock as a factor in the general geological situation. We apprehend the physical world very differently from the way events constituting the physical world apprehend themselves. We can do that because our direct experiences of the physical world are interpreted by the vital occasions involved in our nervous systems. In a sense, the vital occasions involved in the nervous system clothes the physical world with rich and meaningful images that are intrinsic to their own nervous mode of functioning.

Thus vital occasions mediate between our minds and the physical world, clothing the abstract structures of the physical world with imaginally meaningfully forms, and allowing us to instruct our bodies by imagining what we want them to do.

Nevertheless, this analysis should not lead us to think that all vital occasions exist only as the “interiors” of physical bodies. When we dream, lucidly or otherwise, and when we have out-of-body experiences, we find ourselves interacting with other beings who also have vital bodies , but who may or may not have physical bodies. Even in the waking world, we experience disembodied vital beings having noticeable effects, for example in ostensible cases of possession, channeling, or other supernormal modes of functioning.

Mental Actual Occasions

Mental occasions are the “stuff” of thinking. Conscious thoughts are the experiences of the high level actual occasions that form part of our personalities. Again, this is an unfamiliar idea, yet we all know how difficult it can be to work in the realm of thought. Sometimes we can intuit a mental pattern, yet it can take time and concentration to crystallize that pattern into a clear proposition. This is why a great deal of effort often precedes an “aha” moment—when the pattern seems to spontaneously fall into place as an insight.

Vital occasions are more responsive to intentions than physical occasions, and mental occasions are even more responsive. However, thinking is not entirely amenable to our volition. It has a kind of inertia, so that even when we realize that one of our habitual ways of thinking is somehow incorrect, our minds easily slip back into old patterns. And anyone who has tried to formulate new thoughts, to answer questions that have not been answered before, knows just how stubbornly mental entities can hold on to the eternal objects to which they have become accustomed.

Mental occasions do not occur only in our own bodies. We also experience thoughts that seem to just float into our minds. An attentive observer may notice that our ability to comprehend certain ideas is enhanced by the presence of certain other individuals. It is as if certain people “radiate” a kind of illumination from their mental occasions, and the mental occasions of our own bodies are affected by it.

As we consider the various grades of occasions making up our bodies, it is useful to recall that the higher the grade, the less abstraction in objectification occurs between entities at that grade. In other words, the higher the grade of the occasions involved in any causal interaction, the more deeply and fully they know each other.[4]

As noted earlier, low-grade, inorganic entities act as if they are almost entirely external to each other so that, for many purposes, they can be treated as little Newtonian BBs that merely collide with each other. As a result, we cannot really identify with the inorganic components of our bodies. (Of course, we do influence these low-grade entities through our empathic and telepathic interactions with the cells of which they form a part. Also, in some rather unusual circumstances, we may psychokinetically influence those low-grade entities directly.)

By contrast, all of the vital entities in our bodies are empathically bonded with each other. For example, if I have a pain in my little toe, my entire body will suffer empathically with the distressed cells in my toe. We could imagine the inside of our bodies as a pool of empathy isolated from other vital matter by the ocean of inorganic occasions in which it is immersed. Note that to the extent that we can feel our bodies, we can identify with them, and to the extent that we can identify with them, they respond to our intentions.

Finally, the mental entities in our bodies are telepathically bonded with each other. They share each other’s thoughts. They are so close to each other that it is easy for us to identify the whole mass of our mental occasions or “matter” as a single “me.” Only sustained attention, such as that exercised in certain forms of meditation and psychotherapy, allows the various mental selves that make up our personalities to be distinguished from each other.

Multiple Levels of Self

Remember, my purpose in this book is to provide a robust metaphysical foundation for understanding the full range of human experience—including, in general, psi phenomena, and more specifically the data that indicate survival of consciousness after death, and subsequent reincarnation. How, then, might we explain the survival of postmortem personality in relation to embodiment?

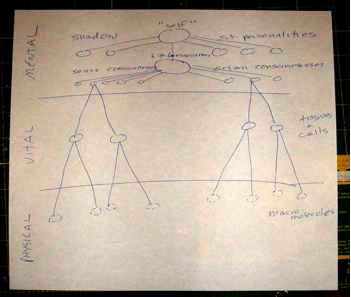

Having conducted a brief phenomenological survey of different types or levels of material, we will now examine a diagram of human personality and its various levels of embodiment.

Figure 3

The large upper, central circle in the diagram (Figure1) represents our self, our basic dominant personality—the one we usually engage the world with—our “ego.” Technically, it is a personally ordered sequence of actual occasions expressing our personality from moment to moment.

However, this conscious ego is not all of who we are. We also have (mostly unconscious) subpersonalities of various kinds. For example, when we lose our temper a different sub-personality is expressed—and later on we may declare: “Oh, that wasn’t me, I didn’t mean it.” We all know what that is like.

Anyone who has trained in this aspect of psychology can watch people shifting in and out of different personalities as their mood changes. In a bad mood people act one way; in a good mood they act another way. Each one of these systems of behavior constitutes a subpersonality. In some forms of psychotherapy, therapists disentangle the sub-personalities, give them names, and help them to communicate with each other. When successful, it leads to personality integration. Some of our subpersonalities are well integrated, we are comfortable with them. Others we resist and suppress, and these form our “shadows,” the parts of ourselves we don’t like.

Our everyday self is a collection of these subpersonalities. Each truly is a personality in the sense that each is a sequence of actual occasions organized with personal order. These are actual, enduring entities in the mental level of the transphysical world.

These subpersonalities have their own lives in the vital and mental worlds—and sometimes even in the waking world. This becomes really clear in cases of dissociative identity disorder in which one sub-personality (or, perhaps, several sub-personalities working together) takes control of the waking self. The everyday ego becomes just one among multiple subpersonalities, and loses its dominant place. Any of these different subpersonalties can take over, and each has its own quite different memory stream. Sometimes, different subpersonalities in the same body don’t remember each other. Or they might remember one, but not another personality. Dissociative identity disorder is intricate and complex, but it shows us that, in fact, these personalities are separable. I am suggesting that they all have the ontological status of enduring societies of actual occasions in the mental world.

And this leads to two interesting questions: First, what is the relationship between these subpersonalities and the dominant personality that seems to be the central self? Second, when a subpersonality takes control, what does it take over? What is the central entity these subpersonalities struggle to dominate?

Regarding the relationship between them, I suggest that the subpersonalities, like the macromolecules in a cell, are an embodiment of one, highest grade, occasion in the human person—and that is the particular personality I usually refer to as “me” or “I.” This idea is theoretically appealing since it both does justice to our sense of on-going continuity, and to our sense of the shifts and transformations that our personalities undergo.However, this is just a suggestion, because my own introspection cannot clearly distinguish that single, dominant, personality from the others that I detect. Sometimes it seems to me that the role of the dominant personality shifts from one subpersonality to another. For the time being, I will assume that the on-going self is a single, personally ordered society; however, when we come to discuss reincarnation in the next chapter, we will also explore the possibility of a more fluid and discontinuous human identity.

As to the second question, I suggest that the central entity over which the subpersonalities struggle is what Buddhists call the “sixth sense” or manas. I am proposing that there is a personally ordered society of actual occasions—distinct from any of the subpersonalities we have been discussing so far—that functions as the central organizing intelligence for the body. It receives reports from all the sense consciousness (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body) and from the organs, each one of which has its own intelligence (which is also mental because we think with our heart and we think with our belly), along with other miscellaneous consciousnesses. For example, most of us has an idiot-savant that can instantaneously compute trajectories. If somebody throws a ball at us we can catch it—a very complex cognitive function we perform almost instantaneously and unconsciously. We have many such functional subpersonalities.

The “sixth sense” or central consciousness receives reports from the collection of sense consciousnesses, organ consciousnesses, and the semi-autonomous “idiot savant” consciousnesses (such as the one that computes trajectories), and forms a kind of central “control panel” for the body. The various subpersonalities, then, compete over who is going to have a privileged relationship with this “sixth consciousness.”

I want to emphasize that each one of these subpersonalities has a life of its own and is an entity in its own right. We are all collections of such entities. At the mental level, these entities exchange information among themselves, which is to say they have causal effects on each other telepathically.

Take for example, our “eye consciousness.” I am proposing that your eye is its own conscious being. You can very easily test this: Just tell your eyes not to blink. Very soon you will experience the autonomy of your eye-consciousness.

To be sure, eye consciousness is willing to accept a certain level of direction—it will look now this way and now that way—but beyond a certain point it expresses its own intentions or preferences. We know from scientific studies that the operation of seeing is extremely complex. Multiple rods and cones in our eyes see different colors and shapes, and these inputs are transmitted along the nervous system until, somehow or other, we compose a picture of the world.

Even if we challenge the rods and cones theory, we still know that as we perceive the world it is already chunked. I look out my window and I see trees and houses and clouds. The world comes to me pre-packaged. I didn’t do that chunking. I did not analyze the raw data of sensation into a picture of a world already sorted out in various categorized ways. Something else did that. Some embodied intelligence within me assembled a coherent image of the world. I then receive that picture telepathically from the consciousness of that particular “hidden chunker.”

My eye consciousness is actually in telepathic contact with all of my other senses and with the various organs and their moods, and with the autonomous idiot-savant consciousnesses mentioned previously. They all communicate with each other and conspire in creating the visual impression that is then telepathically communicated to the sixth consciousness, and, from there, to me. I, in turn, communicate telepathically to my manas, which then tells my eye consciousness where to look or suggests certain categories of things to look for.

All our subpersonalities have direct access to our manas, our “sixth sense,” and also, sometimes, directly to the various sense-consciousnesses and to our motor consciousnesses. Sometimes one of these subpersonalities will send a message to my voice box and I find myself uttering something I didn’t want it to say. We call such moments “Freudian slips.”

In this chapter, I am trying to give you a feeling for the human body and the human self as a host of intelligences of various grades, interacting non-sensorily with each other.

At the vital level, each one of the sense consciousnesses is embodied in various tissues and various cells, and so forth. In the diagram, these are represented (in a vastly simplified way) by the circles at the vital level. These, in turn, are embodied in systems of macromolecules at the physical level (represented in the diagram by the dotted circles on the physical level). Throughout this complex of relationships, telepathic and empathic communication is happening all the way up and all the way down.

This is a new way to understand, and to experience, what it means to be human. It is in radical contrast to what we learn from materialistic science—which tells us that, from my head on down to my cells, my molecules, and my atoms, it’s all basically dead stuff. Somehow, all of these non-conscious automatic events are funneled to my brain and then some miracle takes place whereby the electro/chemical activity in my brain is transformed all at once into an experience. This is a pretty standard summary of the scientific “explanation” for consciousness offered by materialists. However, it is fundamentally incoherent. It makes no sense whatsoever. It explains nothing.

Yes, we know from physiology that every rod and cone in the eye picks up something specific like a certain color, shape, or edge. Let’s accept that. But we still have to explain how all these little impressions (redness, straightness, or whatever) can be integrated into a whole picture of the world. How is that possible? How are the separate bits of information bound together?

If my perception of the world is reduced to nothing but electrical impulses, and if those electrical impulses are all that is transmitted through my nervous system, I don’t see how it would ever be possible to reassemble an image of the world from those nervous impulses. It’s a “Humpty Dumpty” problem.

But now let’s look at this in terms of process metaphysics. I am proposing a much more coherent, if more complex, explanation. I am saying that we are living (vital) and intelligent (mental) entities all the way up and all the way down. Can we reconcile this panpsychist view with what we know from physiology?

Let’s say that each nerve ending in my eyeball is (in each moment of its existence) organized by an actual occasion. And, since every actual occasion takes in the whole universe, then each actual occasion in my eyeball takes in the whole universe.

Because the interests of the actual occasion organizing a cell in my eyeball is highly influenced by my aim, it will pay attention to significant forms such as color and shape. When that occasion objectifies in me, I will prehend it as that color or shape. Insofar as a sensory cell functions prehensively for me, it performs an act of abstraction. However, in contrast to the standard story of physiology, the nerve cells do not transmit electrical impulses alone. On the contrary, I am proposing, the nerve cells transmit an experience of the whole world in which, say, a color is highlighted. Another cell then passes on an experience of the whole world in which a shape is highlighted. And so on . . . Because they are all perceptions of the entire world, they can each be coordinated and synthesized into a coherent composite appearance.

The nervous system, therefore, transmits not only electrical impulses; it also transmits experiences. The idea of an electrical impulse flowing through the nervous system is an abstraction from what is really happening. Carried along with that electrical impulse is a flow of feelings, an empathic and telepathic transmission of experience that is then built up into a complex appearance of the world as it travels through the body. All of these different experiences, each of which is an experience of the whole world, highlighting some different abstraction from it, can be assembled into a picture that is then synthesized by my sixth-sense consciousness and transmitted telepathically to my dominant personality.

Admittedly, this is a very different understanding of physiology. Its great advantage, however, is that it transforms and solves the perennial mind-body problem. It does not try to explain experience according to a mathematical computational model. Perception is accounted for instead by the transmission of experience. In fact, in this new model, all energy is the transmission of experience from actual occasion to actual occasion.

We can trace electrical energy going through the nervous system but that is simply a physical accompaniment to the transmission of experience. This transmission of experience allows us to have continuity with our own past. The person I was a moment ago is telepathically and empathically flowing into the person I am now. That is the way the experience of the world is transmitted through my body up to my dominant consciousness.

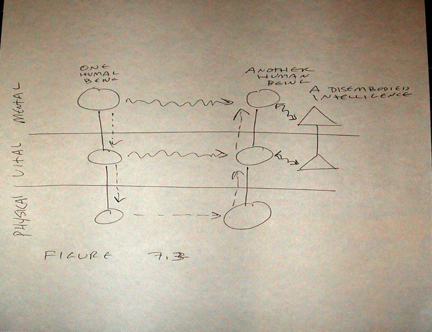

Figure 4

In Figure 2, I have simplified my already abstract representation of people by showing just the mental body, the vital body and the physical body. I have also shown two different embodied humans.

Let’s say we had two different human beings side by side. Ordinarily, we would imagine that if Person 1 thinks something and wants to communicate it to Person 2, the process (simplified) would be somewhat as follows: The thought (at the mental level) would be transmitted down through the body (vital level), and then spoken out into the air (physical level). Next, Person 2 hears the air vibrations (physical level), and this triggers events in the nervous system (vital level), which are, in turn, transmitted up to his or her mind (mental level). This is represented by the dotted line in the diagram.

Now, while this kind of communication undoubtedly does take place, it is far from complete. Rather than being confined to this sensory transmission pathway through physical space, in transpersonal process metaphysics communication in the form of causal interactions is occurring simultaneously across all levels directly. In other words, even while the sensory channels are operating, there is direct telepathic mind-to-mind communication happening at the mental level, as well as direct empathic body-to-body communication taking place at the vital level. In addition to all of this, our sub-personalities are carrying on elaborate simultaneous interactions. In the diagram, some important subsets of these interactions are represented by the wavy lines.

Our bodies are our personal unconscious. We are literally steeped in a complex and rich ocean of feelings, emotions, and thoughts that are not “our own.” What we normally assume to be “outside” is constantly streaming into and informing what we assume to be our private “inside”—and vice versa. In psychology, this field of complex communications is referred to as the personal unconscious, which is itself embedded in an extended web of the collective unconscious.

I have come to realize that my body is an ocean of intelligence, and I sort of ride or surf on it. This ocean of intelligence is my “unconscious.” The more I can bring my own intelligence into effective presence in my body, the more all the various intelligences in my body can be coordinated in my experience and self-expression.

Using this model in psychology—for example, working with subpersonalities—we can begin to see its broader applications. Remember, too, there are also other unembodied transphysical entities—reported in the literature as cases of succubi, incubuses, angels, demons, disincarnate human beings and so forth. These can mimic our own subpersonalities. Sometimes we can’t tell whether a voice in our head is our own or somebody else’s. Sometimes it is obvious, sometimes not. In the diagram, one of these disembodied beings is represented by the linked triangles.

Furthermore, we can share subpersonalities with each other. For example, I have a friend who is very critical of himself. And that friend, in my psyche, is often critical of me. Perhaps, however, I am sharing his critic with him. We may be sharing a common subpersonality.

This new way of understanding human existence opens up fascinating horizons for the study of psychology. It also alerts us to the much greater range of causal effects recognized in transphysical process metaphysics.

To be sure, efficiently causal interactions among the low-grade actualities do constitute the physical world. But transpersonal process metaphysics goes further and supplements these causal interactions with three other categories of causal relations.

• Efficiently causal relations among medium-grade occasions, uniting the living world in a network of empathy.

• Efficient causal relations among high-grade occasions uniting the living world in a network of telepathy.

• Final causes, which allow high-grade occasions to bind lower grade occasions into systems of prehensions, producing the phenomenon of embodiment.

We need all of these different causal operations in order to make reincarnation and life after death intelligible.

We have come a long way in our investigation into the new metaphysics. Specifically, we have established the coherence and plausibility of transphysical worlds (in addition to the physical world), and have seen how human beings, while constituted of inorganic entities, nevertheless simultaneously inhabit transphysical vital and mental worlds. Further, we have seen that these transphysical worlds are not dependent on (or, in the technical jargon of modern philosophy, are not “supervenient” on) physical embodiment. In short, human personalities can exist independently of physical, inorganic atoms and molecules, and, therefore, can survive the dissolution of physiological bodies.

What happens then? In the next chapter, we will turn attention to the age-old idea of reincarnation—and see how the new metaphysics might illuminate the notion that “something” survives death and can be embodied in successive lives.

17

[1] See Radical Nature, pp. 215-238, for an accessible summary of key ideas in Whitehead’s process metaphysics.

[2] Sri Aurobindo, Synthesis of Yoga, 5th ed., Wisconsin: Lotus Lights Publications, 1999

[3] If we interpret “frequency” to be a measure of the “cycle time” of actual occasions, the in terms of transphysical process metaphysics, the higher the grade of an occasion, the lower its frequency will be. This is quite the opposite of usual “New Age” way of speaking.

[4] In the language of Teilhard de Chardin, the higher the grade of the occasions involved the more “radial” and the less “tangential” are their interactions.